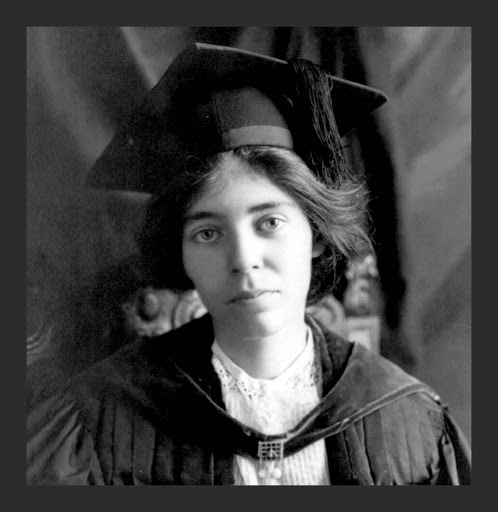

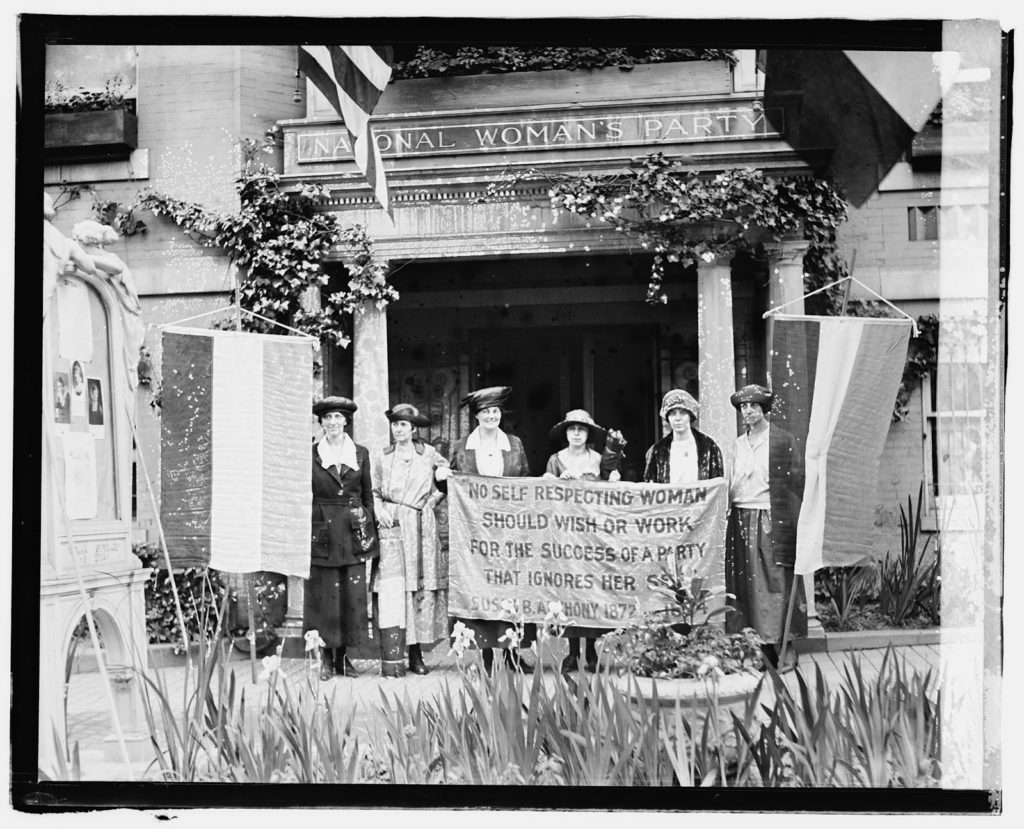

Paul returned to the United States imbued with the radicalism of the English suffrage movement and a determination to reshape and re-energize the American campaign for women’s enfranchisement. While studying at the University of Pennsylvania, she joined the National American Women’s Suffrage Association (NAWSA), one of the leading national organizations working for women’s suffrage. Quickly appointed to lead the Congressional Committee, Paul took charge of working for a federal suffrage amendment, which at that time was a secondary goal of NAWSA’s leadership which prioritized enfranchisement state by state.

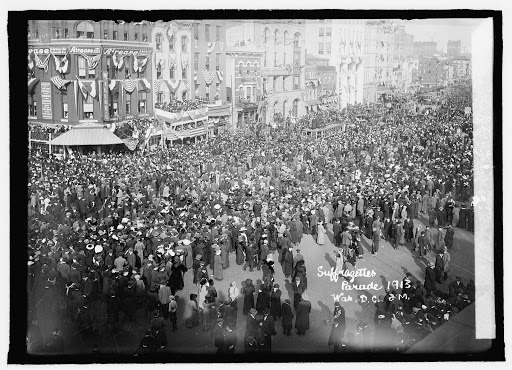

In 1912, Alice Paul joined her NAWSA colleagues Lucy Burns and Crystal Eastman in a move to Washington, D.C. With little funding and in true Pankhurst style, Paul and Burns quickly got to work organizing a publicity event guaranteed to gain maximum national attention. The well-matched pair designed a massive and elaborate parade for thousands of women to march up Pennsylvania Avenue on March 3, 1913, the day prior to the inaugural parade of President-elect Woodrow Wilson.

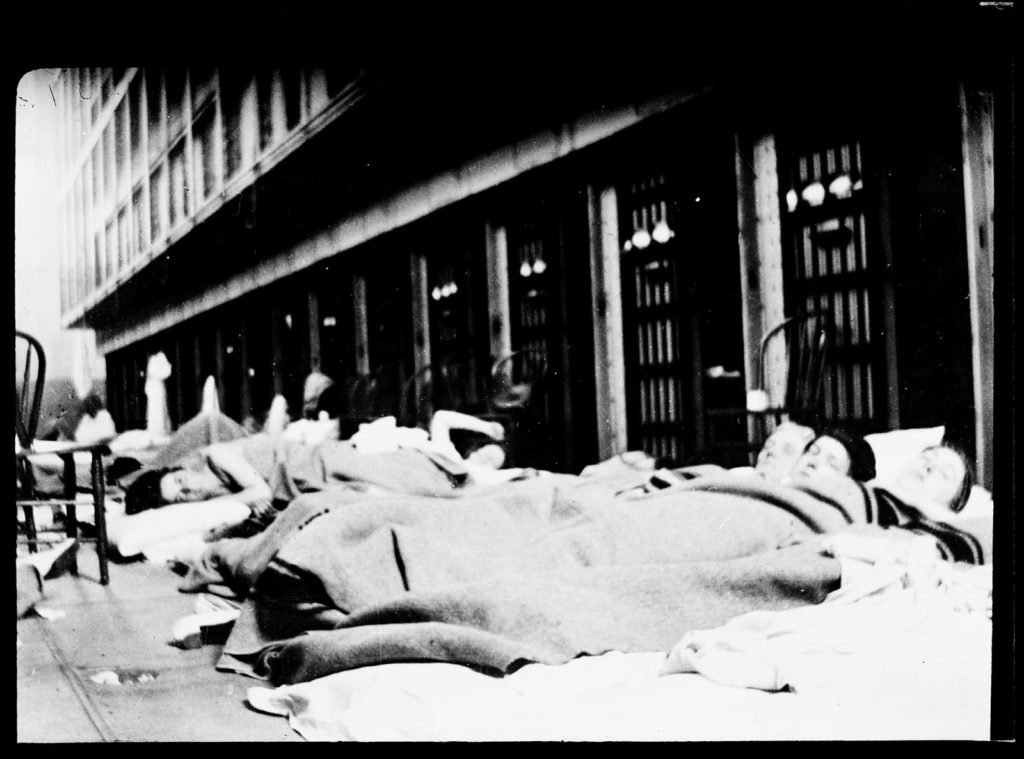

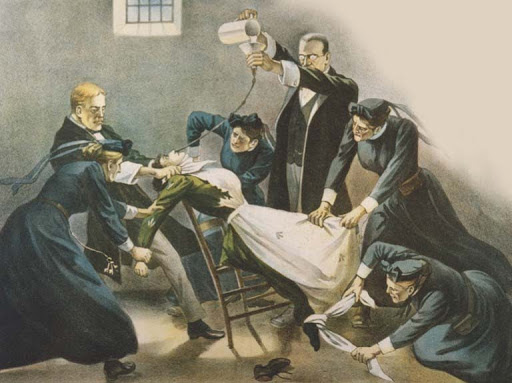

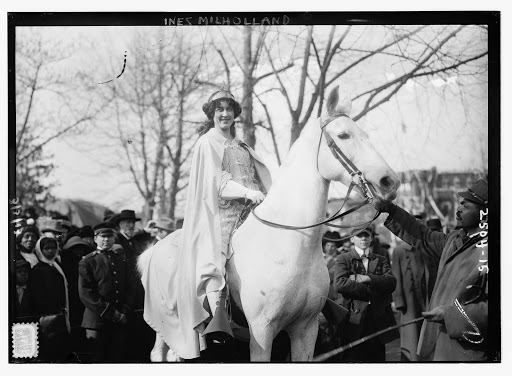

The suffrage procession was led along the parade route by Inez Milholland, a lawyer, activist, and socialite devoted to the cause. Symbolically dressed in Greek robes and astride a white horse, Millholland and the suffragists quickly found the parade route lined with hundreds of male onlookers who were not supportive of their cause. The parade made it only a few blocks before the crowd began to attack the suffragists, first by shouting insults and obscenities, and then with physical violence and assault, all while police officers stood by and watched.

The melee made headlines in newspapers across the country the following day, and women’s suffrage became a popular topic of discussion among politicians and the general public alike.