National Woman's Party

HOW THE PAST INFORMS THE PRESENT

The National Woman’s Party (NWP) fought for women’s rights for more than a century. Starting in 1913, members marched, picketed, and demanded gender equality, and used those lessons, triumphs, and victories to carry their work forward.

Founded in the crucial final years of the suffrage movement by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the National Woman’s Party played a groundbreaking role in securing passage of the 19th Amendment and women’s Constitutional right to vote. The NWP built a membership of committed supporters that mobilized across the United States in support of women’s suffrage, using many of the same tactics used today – protesting, marching, and organizing – to advance women’s rights.

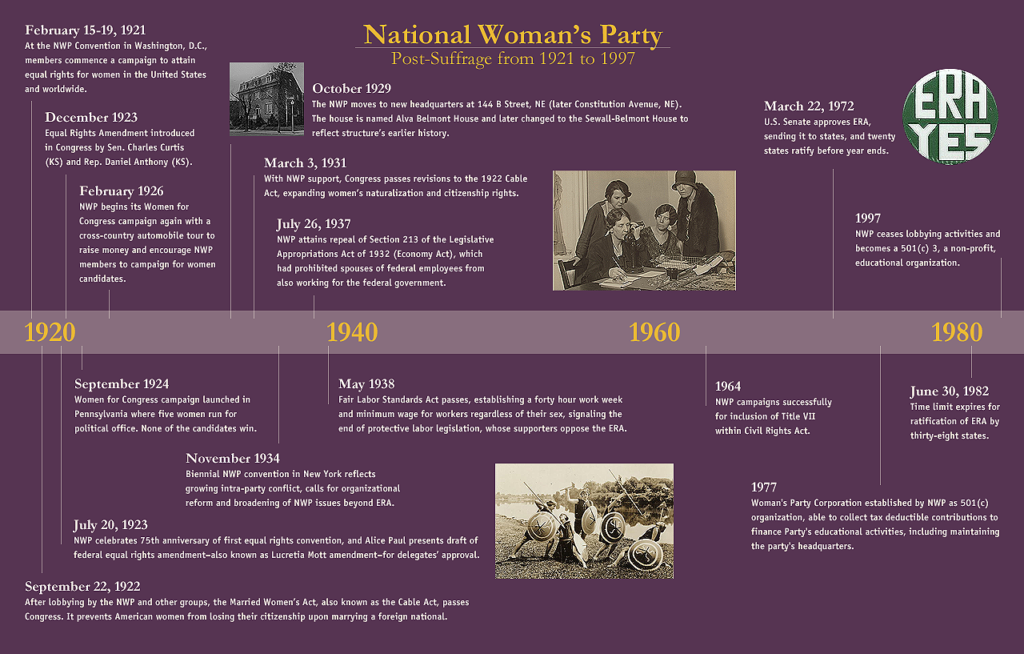

After 1920, the NWP strategically used legal, lobbying, and mobilization campaigns to advance equal rights in the United States and internationally. Following ratification of the 19th Amendment, the NWP moved on to fight for full Constitutional equality for women through the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Members drafted legislation to end labor discrimination and pay inequity; researched and fought unequal laws related to marriage, citizenship, and property rights; and organized international women’s rights campaigns.

The National Woman’s Party ceased operation as an independent non-profit in 2020. Today, its legacy is maintained by three institutions:

- the Alice Paul Institute, which holds the NWP trademark and continues its mission to inspire action to advance gender equality

- the National Park Service, which stewards the NWP’s former headquarters, now known as the Belmont-Paul National Equality Monument

- the Library of Congress, which holds the archives of the NWP and is working to make them available to the public as digital resources

The NWP’s goal of securing full gender equality under the Constitution remains unrealized. The NWP’s goal of full equality for women under the law, and the cornerstone campaign defining Alice Paul’s vision – the ERA – is within reach. Now, as issues of women’s equality have once again moved to the forefront, history compels us to continue the work of the NWP’s founders.

The NWP's Fight for Equality

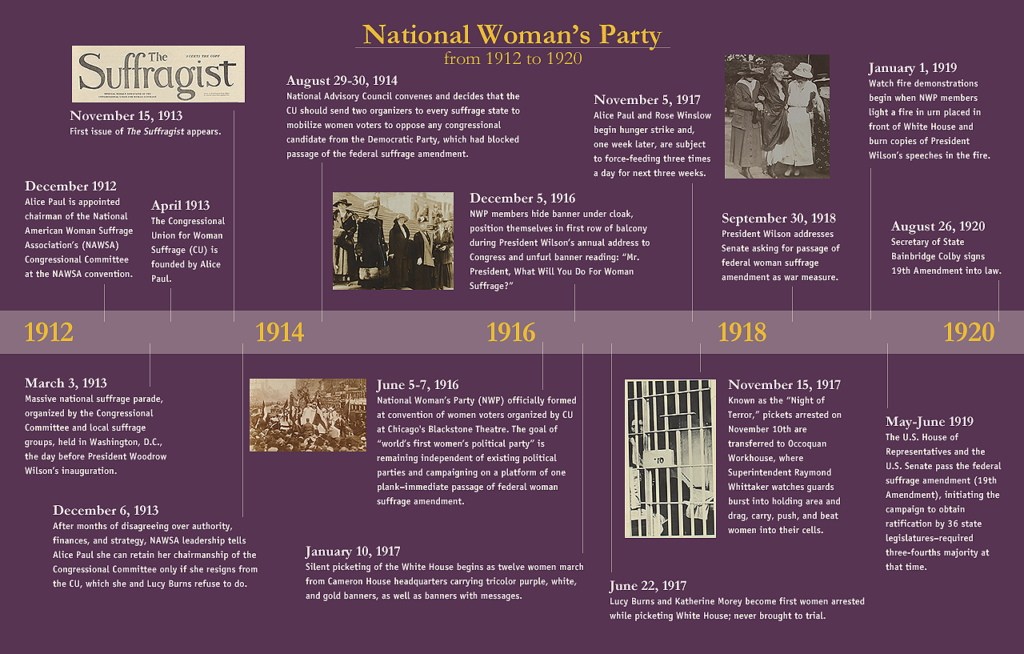

Alice Paul was a well-educated Quaker woman working and studying in England in 1907 when she became interested in the issue of women’s suffrage. She met Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters, Christabel and Sylvia, who were causing controversy throughout England with their militant tactics to secure the vote for women. Paul’s participation in meetings, demonstrations and depositions to Parliament led to multiple arrests, hunger strikes, and force-feedings.

She returned to the United States in 1910 and, after completing a Ph.D. in Economics at the University of Pennsylvania in 1912, turned her attention to the American suffrage movement. After the deaths of the two great icons of the movement—Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1902 and Susan B. Anthony in 1906—the suffrage movement was languishing, lacking focus and support under conservative suffrage organizations that were concentrating only on state suffrage. Paul believed that the movement needed to focus on the passage of a federal suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution. After joining the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and assuming leadership of its Congressional Committee in Washington, D.C., Paul created a larger organization, the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. Paul’s tactics were seen as too extreme for NAWSA’s leadership and the Congressional Union split from NAWSA in 1914.

In 1916, the Congressional Union formed the Woman’s Party, comprised of the enfranchised members of the Congressional Union. In 1917, the two organizations formally merged to form the National Woman’s Party (NWP). From the Pankhursts, Paul adopted the philosophy to “hold the party in power responsible.” The NWP would withhold its support from the existing political parties until women had gained the right to vote and “punish” those parties in power who did not support suffrage. Under her leadership, the NWP targeted Congress and the White House through a revolutionary strategy of sustained dramatic, nonviolent protests. The colorful, spirited suffrage marches, the suffrage songs, the violence the women faced (they were physically attacked and their banners were torn from their hands), the daily pickets and arrests at the White House, the hunger strikes and brutal prison conditions, the national speaking tours and newspaper headlines—all created enormous public support for suffrage.

In 1920, the 72-year struggle ended with the ratification of the 19th Amendment, the “Susan B. Anthony” Amendment, granting women the vote. Paul believed that the vote was just the first step in women’s quest for full equality. In 1922, she reorganized the NWP with the goal of eliminating all discrimination against women. In 1923, Paul wrote the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA), also known as the Lucretia Mott Amendment, and launched what would be for her a life-long campaign to win full equality for women.

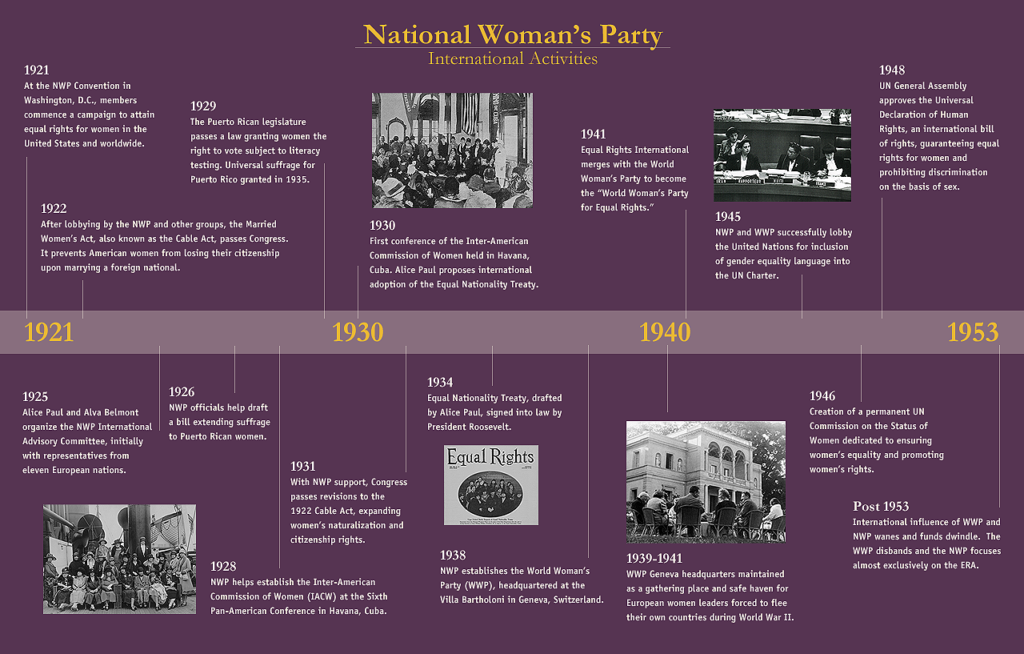

In addition to working on issues affecting American women, the NWP was extensively involved in the international women’s rights movement beginning in the early 1920s. In 1928, the NWP assisted in the establishment of the Inter-American Commission of Women (IACW), which served as an advisory and policy-planning unit on women’s issues for what is now the Organization of American States. The NWP sought equality measures for women at the League of Nations through Equal Rights International and the International Labor Organization. The Party also provided assistance to Puerto Rican and Cuban women in their suffrage campaigns. In 1938, Alice Paul founded the World Woman’s Party, which, until 1954, served as the NWP’s international organization. In 1945, Paul was instrumental in the incorporation of language regarding women’s equality in the United Nations Charter and in the establishment of a permanent UN Commission on the Status of Women.

Moving forward

Read more about the Alice Paul Institute’s acceptance of the NWP trademark and commitment to carrying on the organization’s legacy here.

All photographs from the Library of Congress