Six Influential AAPI Women in Suffrage History

May is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, a celebration of the innumerable contributions of Asians and Pacific Islanders to America’s history—including those made to the decades-long fight for women’s right to vote. An often underrepresented group in the dialogue surrounding the suffrage movement, the AAPI community played a critical role in advocating for gender equality in the United States. As such, we’ve put together a list of six pioneering AAPI women who joined the suffrage movement and dedicated their lives to fighting for equality.

Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee (1897-1966)

Perhaps one of the most well-known AAPI suffragists in the movement, Dr. Mabel Ping-Hua Lee immigrated to the United States on a scholarship when she was only nine years old. By the time Lee reached 16, she was heavily involved in the Suffrage Movement. Lee led suffrage parades, spoke on behalf of women’s suffrage and equality, and published essays on the topic in her school’s paper. Despite her essential role in lobbying for the passage of the nineteenth amendment, Lee was still barred from voting when Congress finally ratified the amendment in 1920.

At the time, the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act still prohibited Chinese immigrants from becoming citizens, thus excluding Lee from exercising her right to vote. Regardless, Lee felt that advocating for suffrage was essential to what she considered to be a fair and equal society; she believed that even if she herself could not immediately benefit, the ratification of the nineteenth amendment was still an important step in creating a universal egalitarian nation. Chinese Americans were granted the right to vote in the U.S. in 1943 with the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, though there are no records indicating whether Lee ever did vote.

Lee went on to graduate from Columbia University in 1921, becoming the first Chinese American woman to graduate with a PhD in economics. It was ultimately her goal to return to China and promote education equality for women, but when her father passed away, Lee instead assumed the role of director for New York City’s First Chinese Baptist Church. In this position, she focused her attention on supporting and advocating for the local Chinese American community.

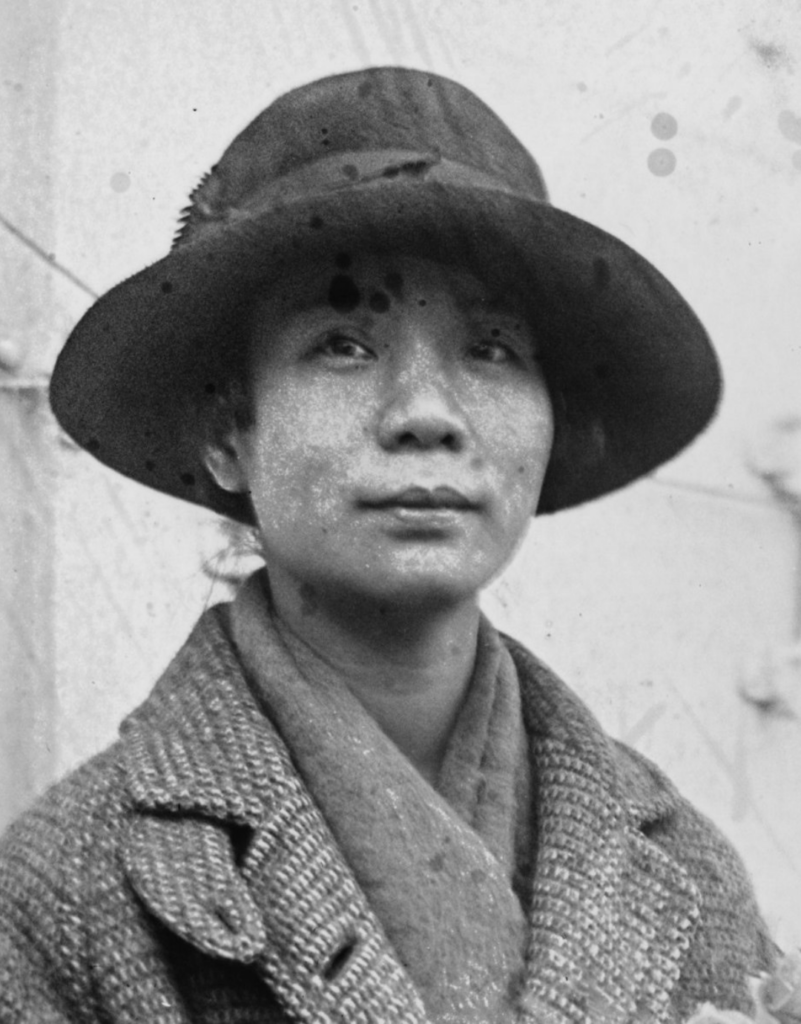

Tye Leung Schulze (1887-1972)

Born in San Francisco in 1882, Leung was the first Chinese American woman to vote in the United States. After running away from home in her early teens when her parents arranged for her to marry an older man, Leung sought refuge at San Francisco’s Presbyterian Mission Home. There, she began her work in activism, aiding the church in its work to free Chinese women from sex slavery. In 1910, Leung became the first Chinese woman employed by the federal government through a position at Angel Island Immigration Station working as a translator for Chinese immigrants.

A year after California granted equal suffrage to U.S. citizens, Leung made history as the first Chinese woman to cast a vote in the U.S., and possibly even the entire world. After voting, Leung was interviewed about her experience and remarked:

“My first vote? Oh, yes, I thought long over that. I studied; I read about all your men who wished to be president. I learned about the new laws. I wanted to know what was right, not to act blindly. I think it right we should all try to learn, not vote blindly, since we have been given this right to say which man we think is the greatest. I think too that we women are more careful than the men. We want to do our whole duty more. I do not think it is just the newness that makes use like that. It is conscience.”

Komako Kimura (1887-1980)

Despite only spending a few years in the United States, Japanese suffragist Komako Kimura had a major impact on the American suffrage movement, as well as the suffrage movement in Japan. Kimura was a famed performer who gained attention for her controversial theatrics and shows. She, along with fellow Japanese feminists Nishikawa Fumiko and Miyazaki Mitsuko, started what was known as “The True New Women’s Association.” The women published a magazine, similarly entitled “The New True Women,” in which Kimura promoted female liberation.

Through writing, theatrics, and public speeches, Kimura advocated for gender equality in Japan and began lobbying for women’s suffrage. When Kimura visited the United States in 1917, she was inspired by the tactics of the American suffragists. During her visit, Kimura marched in a suffrage parade and met with Jeanette Rankin as well as President Woodrow Wilson. The following year, Kimura’s work became the subject of widespread attention in Japan when Kimura was arrested for refusing to close a performance of her play criticizing the Japanese government entitled “Ignorance.” During her trial, Kimura acted as her own defense. Kimura articulated her position so well that the trial in turn only helped to further her cause and was regarded as a successful push for women’s suffrage in Japan. After her trial, Kimura spent eight years living in the U.S., where she helped advocate for suffrage in the American women’s suffrage movement. She also continued acting and would perform at Carnegie Hall and on Broadway.

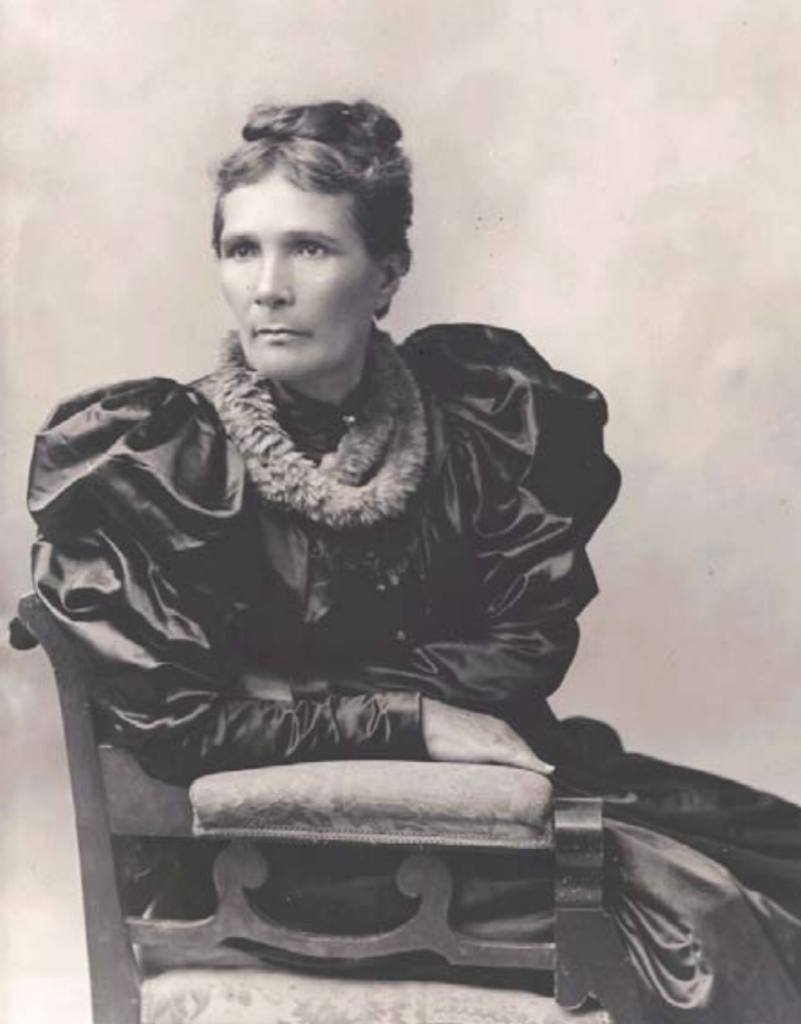

Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett (1861-1929)

Wilhelmina Kekelaokalaninui was born in 1861 at Lihue, Kauai in the Kingdom of Hawaii to a prominent Hawaiian family. After Hawaii was annexed to the U.S., Dowsett became interested in the suffrage movement. In 1912, Doswett founded the Women’s Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai’i (WESAH), which was Hawaii’s first local suffrage club. The following year, the club became an official affiliate of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), and attracted the attention of suffragists like Carrie Chapman Catt and Susan B. Anthony.

By 1919, Dowsett and the work of WESAH had successfully prompted President Wilson to sign a bill granting Hawaiian residents the opportunity to decide for themselves on the matter of suffrage. The movement was stalled, however, when territorial legislators disagreed over specifications of suffrage. White male legislators were concerned about women’s suffrage in Hawaii leading to Native Hawaiians re-claiming political power. Additionally, many white legislators and suffragists were against granting Asian women the right to vote. In response, Dowsett and 500 other suffragists flooded the House floor in protest of the delays. Dowsett continued to work with WESAH to lobby for women’s suffrage until the 19th Amendment was finally ratified in 1920. Hawaii’s political power, however, was still restricted and would remain so until it gained statehood in 1959.

Emma Kaili Beckley

Nakuina (1847-1929)

Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina came from a notable Hawaiian family and helped forward the suffrage movement in the Territory of Hawaii. Nakuina’s involvement in the movement arose after she hosted a party for leading suffragist Almira Hollander Pitman and her husband. The party attracted the attention of women like Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett and helped garner support in the rest of the U.S. for women’s suffrage in Hawaii.

Aside from her involvement in advocating for women’s suffrage, Nakuina is known for being the first female judge in Hawaii under America’s rule. She was also a writer of Hawaiian culture and folklore and served as the first female curator of the Hawaiian National Museum.

Patsy Mink (1927-2002)

Though her political career began several years after the 19th Amendment passed, Patsy Mink was a lifelong advocate for gender equality, a supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, and the author of numerous bills that establish and protect women’s rights. Born in Pa‘ia, Hawai‘i Territory to second-generation Japanese immigrants, Mink was the first woman of color elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and the first Asian American woman to serve in Congress.

Mink faced discrimination early in life for both her race and gender, inspiring her to take an interest in politics and expanding civil rights. Throughout her political career, Mink pioneered progressive legislation that continues to impact America to this day. Notably, Mink helped author Title IX, the Early Childhood Education Act, and the Women’s Educational Equity Act.